Preliminary report on the 2021 breeding season

This report provides a preliminary assessment of the 2021 breeding season in terms of population sizes and breeding success, comparing this year’s results to the averages recorded over the previous five seasons.

The primary aim of BTO surveys is to monitor changes in the health of Britain’s birds, tracking declines and increases via the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) and exploring the factors driving them through bird ringing and nest recording. The long-term trends in abundance, survival and breeding success generated by these schemes are presented on the BirdTrends webpages.

How do we monitor the breeding season?

All of the data presented here are collected by BTO volunteer ringers and nest recorders and we are extremely grateful for their efforts, both in collecting the data and submitting it promptly. Numbers of adult birds are monitored by qualified bird ringers running a network of approximately 120 Constant Effort Sites (CES) across Britain & Ireland between May and August. As their effort is standardised annually, the number of birds caught in each year provides an accurate measure of changes in abundance. Recaptures of birds ringed in previous years also allow survival rates to be calculated. The timing of nesting and the number of fledglings reared during each breeding attempt is monitored by over 650 participants in the Nest Record Scheme (NRS), each of whom locates nests to count the eggs and young inside at regular intervals. The ratio of juvenile to adult birds caught on CESs provides a second measure of breeding success that also takes into account the number of successful breeding attempts made per adult (as many species attempt to rear more than one brood per season) and the survival of young birds immediately after fledging.

CES covers 24 woodland, scrub and reedbed species, while NRS covers 150 species breeding across all habitats, from gardens to remote hillsides. Not all of the CES and NRS data collected in 2021 have been received yet, so these results are based on a subset of sites and species for which we currently hold sufficient information to analyse.

What was the weather like in 2021?

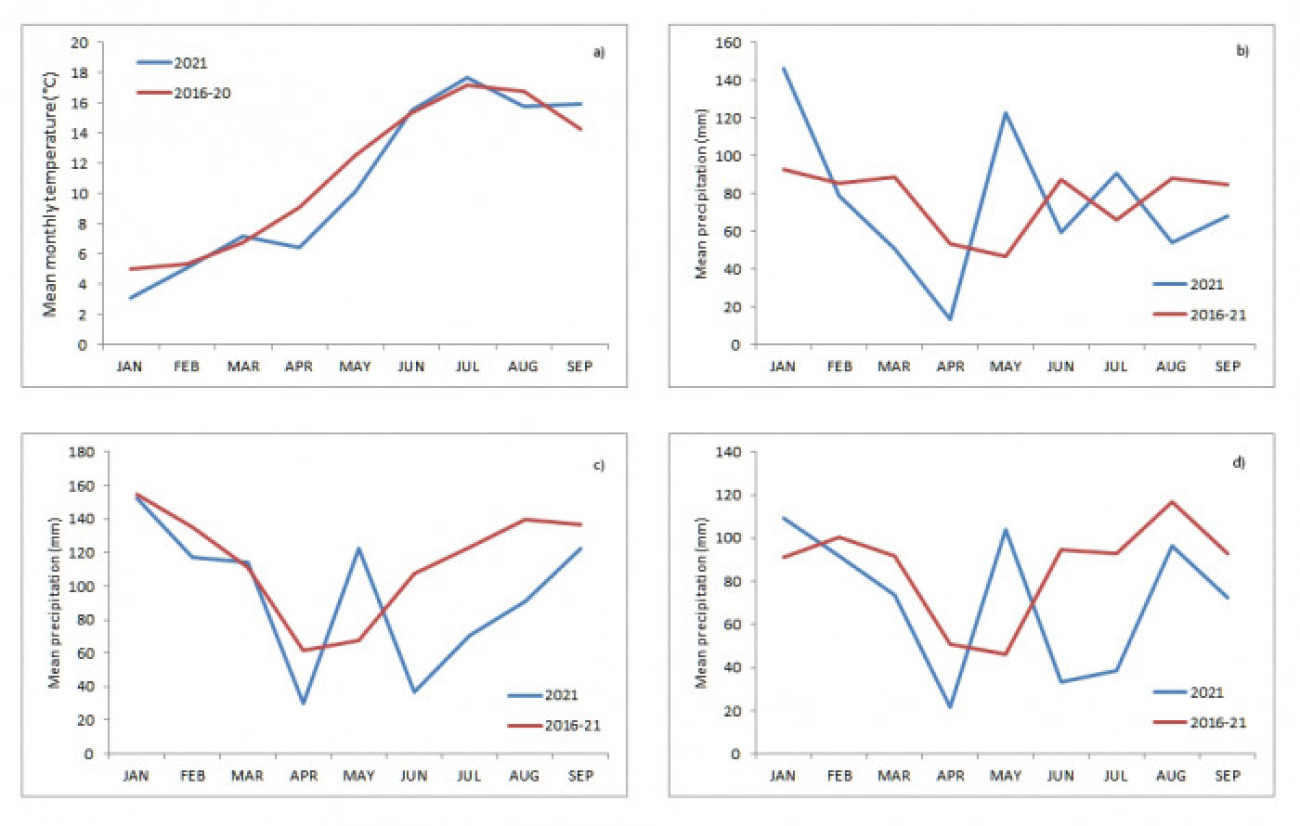

Winter 2020-21 was colder than average, with frequent frosts and snowfall affecting some areas as well as higher than average rainfall totals for the UK as a whole. Cold weather continued into the breeding season; regular frosts resulted in April 2021 being the coldest since 1989 and May 2021 being the coldest since 1996. March and April saw lower than average rainfall totals, while May was far wetter than normal, the UK experiencing 171% of the average monthly rainfall. The weather in summer was variable, with Scotland seeing temperatures rise well above the mean with reduced rainfall, while south-east England was far cooler and wetter than average; Wales, Northern Ireland and northern England were also drier than average. Conditions did improve in late summer; July 2021 proved to be the equal fifth warmest July since 1884 and included an all-time record high temperature in Northern Ireland (31.3°C). Summarised weather data for the Republic of Ireland in 2021 are not yet available.

The 2021 season

After the disruption to the 2020 breeding season caused by the Covid pandemic, the majority of ringers and nest recorders were able to get back to their sites in 2021. These preliminary trends include data from 92 CES sites and NRS information from 655 recorders.

Migrant abundance

The numbers of individuals encountered during CES sessions was significantly higher than the five-year mean (2016–20) for four migratory species in 2021 (Table 1), the long-distance migrants Whitethroat, Sedge Warbler and Reed Warbler and the short-distance migrant Chiffchaff. Whitethroat has exhibited a significant increase in abundance for the third successive year and exhibited the highest increase (+35%) of all species recorded in 2021. The increased numbers do not appear to have been due to a productive breeding season last year, or to high adult survival over the 202/21 winter, so may relate to higher than average survival of young from 2020. Willow Warbler, a long-distance migrant, was the only migratory species to record a significant decrease in abundance in 2021, but again there is no evidence that this is due to low breeding success in 2020 or reduced adult survival over the following winter.

|

Species |

Adult abundance change (%) |

Productivity change (%) |

Survival change (%) |

|

Migrant warblers |

|||

|

Chiffchaff |

14 |

-22 |

15 |

|

Willow Warbler |

-10 |

-24 |

-9 |

|

Blackcap |

-5 |

-44 |

-1 |

|

Garden Warbler |

-2 |

-35 |

0 |

|

Lesser Whitethroat* |

-2 |

-23 |

-22 |

|

Whitethroat |

35 |

-42 |

31 |

|

Sedge Warbler |

24 |

-34 |

10 |

|

Reed Warbler |

7 |

-21 |

-5 |

|

Other residents |

|||

|

Cetti's Warbler* |

33 |

-20 |

- |

|

Treecreeper* |

20 |

-46 |

- |

|

Wren |

17 |

-32 |

21 |

|

Blackbird |

-8 |

-36 |

21 |

|

Song Thrush |

-1 |

-24 |

-53 |

|

Robin |

4 |

-16 |

24 |

|

Dunnock |

10 |

-35 |

22 |

|

Chaffinch |

-39 |

-14 |

-64 |

|

Greenfinch |

-35 |

1 |

- |

|

Goldfinch |

-1 |

-53 |

- |

|

Bullfinch |

-11 |

-18 |

-1 |

|

Reed Bunting |

-8 |

-17 |

28 |

|

Resident tits |

|||

|

Blue Tit |

7 |

-23 |

10 |

|

Great Tit |

4 |

-40 |

-1 |

|

Willow Tit* |

-28 |

-42 |

- |

|

Long-tailed Tit |

4 |

-32 |

-30 |

Resident abundance

CES results indicate a more mixed year for resident species, with three displaying significant increases in abundance and three exhibiting significant decreases compared to the five-year mean (2016–20; Table 1). Cetti’s Warbler achieved the highest resident rise in abundance (+33%), with smaller increases recorded for Wren and Dunnock. It is not possible to produce a survival estimate for Cetti’s Warbler from CES records, but neither Wren nor Dunnock exhibited above average adult overwinter survival and none of the three species displayed increased breeding success in 2020, so again, juvenile survival may be the driver. Despite not recording a significant increase in abundance relative to the five-year mean, absolute numbers of Treecreepers were higher than in any previous year since CES monitoring began in 1983.

Chaffinch and Greenfinch abundance continues to decline significantly. Once again, the number of adults of both species encountered were lower than in any previous year and the last five seasons represent the five lowest adult capture totals on record; Greenfinch numbers have declined to such an extent that it is no longer possible to generate adult survival figures for this species. Data for Chaffinch indicate a 64% drop in adult overwinter survival, and it is possible that the decline in Greenfinch is also partly related to poor overwinter survival of adult birds, possibly due to the continued effects of the devastating trichomonosis outbreak that began in the mid-2000s. The other resident species displaying a decline in numbers in 2021 was Bullfinch, which may be linked to a significant reduction in productivity recorded during 2020.

Late breeding season

NRS data indicate that the overall trend in 2021 was for a delayed breeding season, as would be predicted during a cold spring (2016–20; Table 2). Four migrant species (Sand Martin, Swallow, Reed Warbler and Pied Flycatcher) exhibited laying dates between three and six days later than the five-year average. It is possible that the cold spring delayed the arrival of some migrants, contributing to a later start to the breeding season, but BirdTrack data do not provide strong support for this, with the possible exception of Swallow. It should be noted that Sand Martin, Swallow and Reed Warbler are multi-brooded species and therefore average laying dates could have shifted later in response to increases in the number of second broods produced, which the clement late summer weather could have encouraged.

Laying dates for five passerines (Blue Tit, Great Tit, Dipper, Meadow Pipit and Chaffinch) were also delayed by between one and eight days, with Meadow Pipit and Chaffinch being the latest, most likely due to the cold winter and early spring weather. Meadow Pipit and Chaffinch, which are slightly later breeders, may also have been impacted the unusually high rainfall in May.

Only two species, Stonechat and Woodpigeon bred significantly earlier in 2021 compared to the five-year mean; for Stonechat, the eight day advance in laying dates represents the earliest first egg dates on record for this species. Woodpigeon breeding seasons are long and complex, and the documented 24-day advance could reflect a curtailed breeding season, rather than one that started early.

|

Species |

Species Laying date days |

Clutch size % |

Brood size % |

Egg stage survival % |

Young stage survival % |

Fledglings produced % |

|

Migrants |

||||||

|

Sand Martin |

5.6 |

-1.4 |

7.1 |

-1.3 |

1.4 |

7.2 |

|

Swallow |

6.1 |

0.4 |

1.1 |

1.5 |

7 |

9.8 |

|

Chiffchaff |

-2.3 |

-0.2 |

0.5 |

1.9 |

-1.5 |

0.9 |

|

Willow Warbler |

3.4 |

8.5* |

0.3 |

-10.2 |

-18.5 |

-26.6 |

|

Blackcap |

-3.6 |

-4.1 |

-7 |

-17.7 |

-14.6 |

-34.6 |

|

Whitethroat |

3.5* |

0.0* |

2.2 |

-0.3 |

-10.6* |

-8.9 |

|

Reed Warbler |

3.1 |

-1.9 |

-3.9 |

5 |

-3.7 |

-2.8 |

|

Spotted Flycatcher |

4.1* |

3.4 |

-2.8 |

-10.6 |

2.7 |

-10.8 |

|

Pied Flycatcher |

5.6 |

-5.4 |

-4.4 |

-3.5 |

6 |

-2.2 |

|

Tree Pipit |

3.5 |

-0.9 |

9.4 |

9.3 |

15.1 |

37.7 |

|

Tits |

||||||

|

Blue Tit |

1.2 |

-1.7 |

-2.9 |

-1.6 |

-5.1 |

-9.3 |

|

Great Tit |

2.7 |

-5.7 |

-10.4 |

-3.4 |

-3.5 |

-16.4 |

|

Long-tailed Tit |

-1.1 |

-0.3 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

2.8 |

|

Other resident passerines |

||||||

|

Jackdaw |

-1.2 |

3.8 |

-2.4 |

0.5 |

-0.8 |

-2.7 |

|

Raven |

-5.1* |

20.4* |

-0.6 |

-22.8* |

2.4 |

-21.4 |

|

Nuthatch |

0.6 |

1.1 |

-2 |

-8.2 |

-10.5 |

-19.5 |

|

Wren |

2.9 |

-0.9 |

1.4 |

-5.6 |

9.1 |

4.5 |

|

Starling |

0.4 |

0.3* |

3.4 |

2.4 |

-11.5 |

-6.3 |

|

Dipper |

5.9 |

1 |

4.5 |

0.3 |

5.5 |

10.6 |

|

Blackbird |

-2.3 |

-0.6 |

0.9 |

2 |

-11.7 |

-9.1 |

|

Song Thrush |

-0.4 |

-1.9 |

-4.8 |

-10.6 |

-9.6 |

-23 |

|

Robin |

1 |

-3 |

3.3 |

-1.4 |

-15.5 |

-13.9 |

|

Stonechat |

-8.3 |

0 |

4 |

-6.4 |

-16 |

-18.2 |

|

Dunnock |

-0.2 |

-4.7 |

-3.6 |

-2.5 |

-10.8 |

-16.1 |

|

House Sparrow |

-1.8 |

-1.1 |

-6.3 |

-2.4 |

-2.8 |

-11.1 |

|

Tree Sparrow |

-1.9 |

-3.5 |

-6.9 |

-6 |

1.1 |

-11.5 |

|

Grey Wagtail |

-3.5 |

-5.1 |

-0.1 |

3.1 |

3.2 |

6.3 |

|

Pied Wagtail |

3.9 |

-1.7 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

-4.9 |

-3.7 |

|

Meadow Pipit |

8.2* |

1.9* |

0.1 |

34.6* |

13.1 |

52.4 |

|

Chaffinch |

8.3* |

-4.6 |

-7.5 |

-4.5 |

-7.1 |

-17.9 |

|

Goldfinch |

2.0* |

3.2* |

7.4 |

8.2 |

-21.7 |

-9 |

|

Linnet |

-1.6 |

-0.6 |

0.2 |

23.6 |

-4.3 |

18.5 |

|

Reed Bunting |

4.1 |

-3.5* |

-0.5 |

0.2* |

29 |

28.5 |

|

Resident non-passerines |

||||||

|

Stock Dove |

2.5 |

-4.7 |

-0.8 |

-6.3 |

12.8 |

4.8 |

|

Woodpigeon |

-24.1 |

4.6 |

4.2 |

-34.7 |

-25.9 |

-49.6 |

|

Owls and raptors |

||||||

|

Buzzard |

5.0* |

46.7* |

-1.6 |

2.8* |

4.5 |

5.7 |

|

Kestrel |

7.3* |

-4.5 |

2.5 |

3.3 |

3 |

9 |

|

Peregrine |

-1.9* |

5.4* |

-3.8 |

-5.4* |

-1.5 |

-10.3 |

|

Barn Owl |

18.9 |

-1.7 |

-1.5 |

-1.3 |

0.1 |

-2.7 |

|

Little Owl |

6.2* |

10.4 |

-0.8 |

6.5* |

-2.1 |

3.5 |

|

Tawny Owl |

11.1* |

1.7 |

0.9 |

-2.7* |

-1.1 |

-2.9 |

|

Waterbirds |

||||||

|

Moorhen |

-2 |

3.9 |

17.9* |

-32.7 |

17.3* |

-7.0* |

|

Coot |

-6.3 |

10.8 |

-20.3* |

-9.3 |

-74.4* |

-81.5* |

|

Waders |

||||||

|

Lapwing |

4.0* |

1.2 |

-18.9 |

-90.4 |

- |

0 |

Poor breeding season

2021 proved to be a disastrous breeding season, with 18 of the 24 species recorded through CES displaying significant declines in productivity compared to the five-year mean (Table 1) and none exhibiting significant increases. Six species recorded their lowest breeding success since CES monitoring began; Willow Warbler, Treecreeper, Wren, Blackbird, Dunnock and Willow Tit. NRS results indicated that four species produced lower than average numbers of fledglings per breeding attempt (FPBA): Blackcap, Blue Tit, Great Tit and Tree Sparrow. For Blackcap and Great Tit, this represents their lowest breeding success since NRS monitoring figures were first produced in the mid-1960s; Great Tit also recorded its lowest ever clutch size in 2021. The cold, wet spring and early summer is the most likely cause of poor offspring production, preventing fledging or increasing mortality of fledglings shortly after they had left the nest. The few species that recorded increased abundance in 2021 may also have experienced increased competition with other pairs, leading to density dependent reduction in productivity. Results in the north were less negative for migrant species recorded on CES, with only Blackcap exhibiting a significant decrease in breeding success. The warmer summer temperatures in Scotland, compared to the rest of the UK and Ireland, might have helped mitigate some of the impacts; results for resident species, which generally breed earlier, were similar across Britain & Ireland. Four species (Sand Martin, Swallow, Tree Pipit and Meadow Pipit) recorded significant increases in FPBA in 2021, all of which breed later into the summer and may therefore have been less impacted by the cold spring.

Help us to monitor birds in 2022

The records used to produce the NRS results are generated by around 700 NRS volunteers, who monitor nests ranging from Blue Tit boxes in gardens to seabird colonies on cliffs. If you haven't tried nest recording before, why not give it a go? Email us for a Quickstart Guide or visit the NRS web pages to find out more.

If you are a qualified ringer with access to an area of scrub, woodland or reedbed where there is the potential to catch at least 250 birds per season, why not register a CES? And if you aren’t able to start your own site, why not consider helping out at an existing one? Contact the CES Organiser for more information.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all Constant Effort Site ringers and nest recorders for their monitoring efforts and for the support of the BTO/JNCC partnership, which the JNCC undertakes on behalf of the Country Agencies. Additional funding for the BTO Ringing Scheme is provided by The National Parks and Wildlife Service (Ireland) and the ringers themselves. The Breeding Bird Survey is run by the BTO and jointly funded by the BTO, the JNCC and the RSPB. BirdTrack is organised by the BTO for the BTO, RSPB, BirdWatch Ireland, SOC and WOS.

Share this page