Monitoring raptors in the UK

- What are raptors?

- The threats that raptors face

- Why we need better raptor monitoring

- Our plans to expand dedicated raptor monitoring

- Donate to the Raptors Appeal today >

What are raptors?

Raptors or birds of prey are carnivorous (meat-eating) birds that usually hunt to eat, catching small birds, mammals, insects, amphibians, reptiles or fish. Some specialise in a particular type of prey: for example, Sparrowhawks are uniquely adapted to hunt small birds, whereas Ospreys are adept at hunting fish. Many birds of prey will also scavenge opportunistically, although some rely more heavily on carrion (already-dead meat) than others, such as Red Kite.

Birds of prey share several physical characteristics that help them find, hunt, and kill their prey, such as incredible visual acuity, sharp, curved talons (claws), and a hooked bill for tearing flesh. However, they range enormously in size: the relatively compact Merlin can weigh as little as 160 g, while the White-tailed Eagle can reach an astonishing 7 kg – 45 times heavier!

Ornithologists have used a mixture of taxonomy (the evolutionary relationships between species) and ecology (behaviour, diet and habitat) to define the group of birds that we at BTO refer to as ‘raptors’.

Interestingly, genetic analyses have shown that falcons like Peregrines are more closely related to parrots than they are to many other raptor species. However, because falcons share a similar ecology with eagles and hawks, they tend to be grouped together. Conversely, birds like skuas are not considered raptors because of their taxonomy, despite sharing habitat and some behavioural and dietary characteristics with raptors like White-tailed Eagles and Ospreys.

Grouping birds together, like raptors, is ultimately a tool to aid in developing surveys, research or conservation. For example, BTO also considers Raven a raptor, even though it is technically a Corvid species. This is partly because of its ecological similarity to raptors, but also because it requires similar monitoring and survey methodologies.

The threats that raptors face

The grace of a Kestrel or a Buzzard hovering, Golden Eagles displaying together over a mountain ridge, the power of an Osprey or a White-tailed Eagle hunting or a Short-eared Owl quartering over a Scottish moorland – these are all incredible moments to experience.

But our birds of prey have a long history of being impacted by a range of issues, including illegal killing, secondary poisoning, habitat and prey loss, and climate change. We have also recently seen the impact of avian influenza on several birds of prey.

Sadly, many of these threats continue to place stress on raptor populations.

Illegal killing

Birds of prey are now protected by law, and reduced persecution has supported increases in Buzzard and Peregrine populations, for example. However, illegal killing continues to have a significant impact on several species.

For Red-listed Hen Harriers, for example, persecution is the main threat to their breeding population, with deliberate and unlawful killing or disturbance reducing the survival of breeding females and the success of nesting attempts. The most recent survey of Hen Harriers across the UK revealed that, despite some encouraging regional increases, the total number of Hen Harriers remains below those recorded in 2004. This population estimate represents only a quarter of the potential population that could be supported by the species’ ideal habitat, with illegal killing likely hampering population recovery in otherwise suitable areas.

Secondary poisoning

Secondary poisoning describes situations where one organism ingests a poison, and in turn, is consumed by a second organism which then suffers the effect of that poison. Raptors are particularly vulnerable to secondary poisoning because of a process called biomagnification, which causes the concentration of a poison in an organism’s tissues to increase at higher levels of a food chain.

The widespread use of anticoagulant rodenticides (rat poisons) is likely to impact many raptors, including those which do not typically feed on rodenticide target species. Research suggests that more than 80% of Sparrowhawks could be contaminated with rodenticides such as difenacoum after eating songbirds that had fed on rodent bait, with potential population-wide effects. The decline in Kestrels in the UK is also thought to be linked to these pesticides.

The effects of historical pesticide use are also seen in today’s raptor populations. Species like Merlin, Peregrine and Sparrowhawk are still recovering from the devastating impacts of organochlorine insecticides like DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), which were used widely in the UK in the mid-20th century. In birds, DDT caused severe thinning in the shells of eggs laid by affected birds, with a corresponding and catastrophic drop in breeding success. Its use was banned in the UK in 1986, but it is still present in soils almost 40 years on.

Habitat loss and climate change

The twin threats of habitat loss and climate change on raptors are not well understood but are known to be affecting many other bird species and biodiversity more widely. We urgently need more data to form a clearer picture of raptor population changes in response to these threats.

Declining populations

In the 1970s, there were fewer than 100 pairs each of Golden Eagles, Hobbies, Hen Harriers and Red Kites. Despite conservation efforts aimed at bolstering raptor populations resulting in some increase in their numbers, many are still struggling to recover.

Nearly two-thirds of the 60 raptor species in Europe have an unfavourable conservation status, and in the most recent (5th) Birds of Conservation Concern UK report, Hen Harrier, Montagu’s Harrier and Merlin are Red-listed and eight more raptor species are Amber-listed.

We clearly need to do more for these iconic birds.

Why we need better raptor monitoring

Many people are surprised to learn that, despite our best efforts, there are significant gaps in our knowledge about birds of prey. Their low population density makes them challenging to survey effectively, and they are often not yet active during the early morning monitoring typical of schemes like the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey. Raptor-specific monitoring efforts are often focused on rare species such as Hen Harrier and Golden Eagle, and widespread species like Buzzard, Sparrowhawk and Kestrel tend to be exceptionally poorly covered. We also need to understand more about demographic rates, like breeding success, as well as numbers of pairs breeding.

The Breeding Bird Survey can currently provide us with basic trends in breeding season abundance for some of the wider-spread raptor species at UK and country scales, but there are a number of reasons why we need additional raptor monitoring information to support raptor conservation.

Breeding Bird Survey survey transect methods are most suitable for small, short-lived songbirds with small breeding territories. For longer-lived species like many raptors that may not breed until two or more years of age, and have large breeding home ranges, it is not possible to convert sightings on transects into numbers of breeding pairs. Sightings from Breeding Bird Survey transects may also include (sometimes large) numbers of non-breeding immature birds. This means that trends produced from Breeding Bird Survey data can confound changes in breeding numbers with changes in annual breeding success for species like Raven and Buzzard.

The raptor monitoring approaches that we are keen to help expand use methods that are appropriate for generating more accurate trends in both breeding numbers and productivity, and for capturing the locations of nests. All of these data types are highly valued by those organisations that work to conserve raptors across the UK.

The limited nature of the data we do have about raptors means that our current understanding of raptor populations is poor: although some species are better monitored, like Hen Harrier, we still need to find the answers to questions such as “Why are Sparrowhawks and Kestrels still declining?” and “What are the main drivers of population change in Ravens?”. As an example, using Scottish Raptor Monitoring Scheme (SRMS) data, we can only produce a fully representative national trend in raptor breeding numbers for one species, the White-tailed Eagle – but we need trends for all species to support their conservation.

As apex predators, raptors are essential parts of ecosystems, with knock-on consequences for wider food webs if their numbers change. To properly map population and distribution changes, to understand the drivers of these changes, and to unpick the impacts of these changes on wider biodiversity, we need to have trends for all raptors across the entire UK.

Learn more about three focal species which would benefit from better raptor monitoring: Kestrel, Sparrowhawk and White-tailed Eagle.

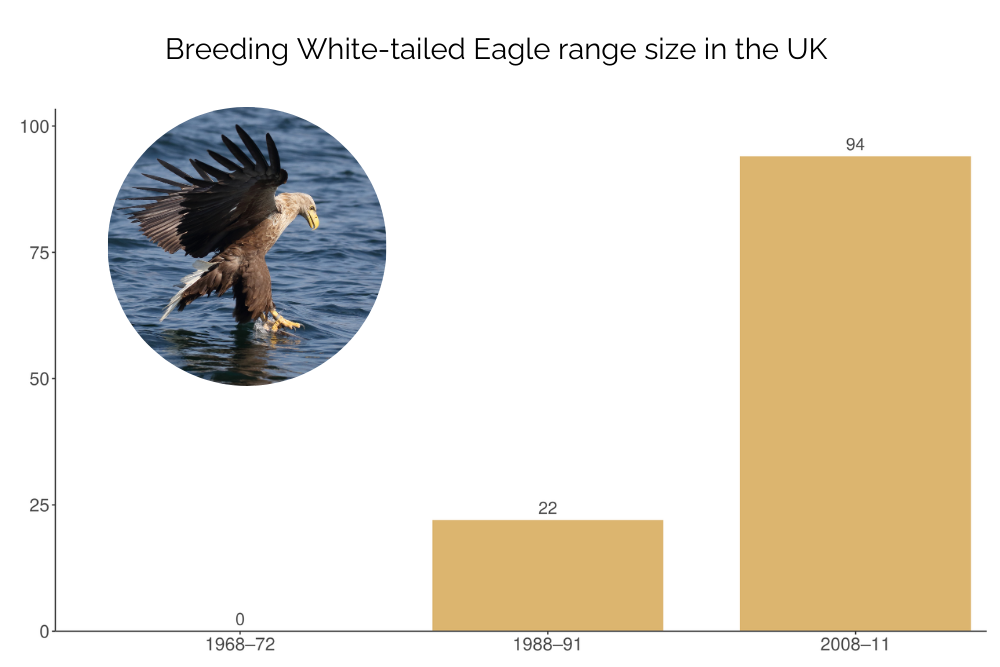

White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla

This iconic raptor was widespread throughout Britain in the Middle Ages, but due to habitat loss and persecution, it was lost as a breeding species by 1916.

Following successful reintroductions, the first on Rum, Scotland, in 1975, we have seen them return to our skies. There are now more than 150 breeding pairs in the UK, although sadly persecution does still occur in some areas.

BTO recently used data from the Scottish Raptor Monitoring Scheme to provide evidence of the effects of highly pathogenic avian influenza on our White-tailed Eagles, showing the disease had a significant impact on breeding success.

A challenge for the future will be to ensure appropriate monitoring can be maintained and expanded as the species further increases its breeding range.

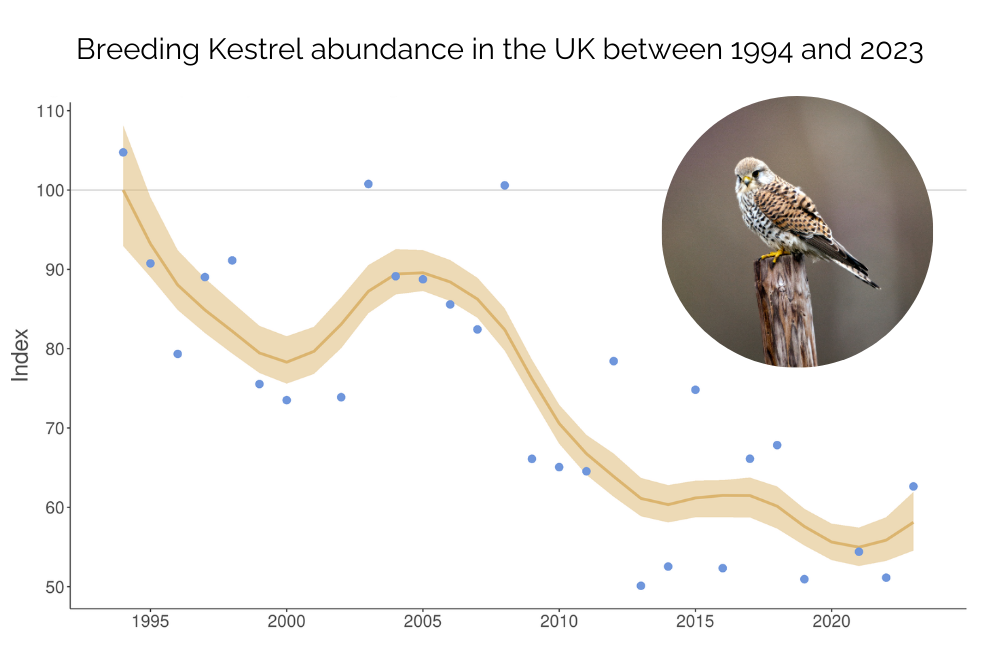

Kestrel Falco tinnunculus

This once-common falcon is often sighted hunting for small mammals along verges. Sadly, its population has declined by more than half since 1970, something that has been linked to agricultural intensification in farmland habitats.

Land management policies can enable land-owners to take up agri-environment options such as buffer strips, uncultivated margins and conservation headlands, helping to provide suitable habitat to benefit Kestrels. However, annual data collected by BTO’s partnership monitoring schemes highlight a continuing decrease in Kestrel numbers, which fell by 40% between 1995 and 2022 in the UK.

The drivers of the ongoing population decline are not understood with certainty, although secondary poisoning through rodenticides (rat poison) is likely to play a part. More research is needed to aid this exquisite raptor, and with less than a handful of existing long-term studies investigating its plight, it is one of the key species for which we are trying to improve coverage through our new patch-based monitoring initiatives.

Sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus

This agile woodland bird has a distinctive flight: a series of powerful, flapping wingbeats interspersed with glides. The species has an important function in ecosystems, helping to maintain the overall health of its prey populations. Many of us will have seen this in action at our garden bird feeders – often with very mixed feelings!

Sparrowhawks suffered a severe population crash in the 1950s and 1960s that was mainly caused by secondary poisoning (consuming prey which had ingested agricultural pesticides such as organochlorides), and were lost from large areas of lowland Britain. Following a ban on the use of organochlorines, toxic and persistent chemicals used in pesticides and herbicides which accumulate in high concentrations at the top of food chains, Sparrowhawk numbers increased until the early 1990s. However, the population again began to fall, and has declined by about 18% in England since 1995.

More research is needed to understand why the population has declined again, but, as secretive birds, Sparrowhawks are challenging to study and therefore receive limited monitoring effort. Developing and growing our patch-based approaches will make a real difference in understanding the needs of this agile ambush predator.

Our plans to expand dedicated raptor monitoring

BTO’s evidence-led and non-campaigning identity as a science and monitoring organisation is extremely valuable when working with a taxonomic group as special and potentially divisive as raptors. It allows us to convene groups of stakeholders, who may sometimes have widely differing views and needs, helping them to coalesce around the common goal of collecting robust monitoring data.

We have a long history of developing high-quality monitoring schemes specific to certain groups of birds, such as the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey, or WeBS, for waterbirds; the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey, or BBS, for widespread terrestrial birds; and the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Seabird Monitoring Programme, or SMP, for seabirds. Our extensive experience developing these surveys gives us a strong foundation to help expand and improve dedicated raptor monitoring across the UK.

We have also been a very active partner in the Scottish Raptor Monitoring Scheme (SRMS) since 2002. The SRMS is a partnership of eight organisations, all committed to monitoring Scotland’s 20 native birds of prey. The SRMS has always operated on a limited budget, and now faces cutbacks when we badly need more investment.

Our role within the SRMS has included leading the collation, analysis and reporting of monitoring data collected by volunteers, and delivering scientifically rigorous information on trends in numbers, range and productivity. Taken together, this information helps us to understand the causes of raptor population change in Scotland. We plan to use our deep experience, gained from more than 20 years of developing coordinated raptor monitoring in Scotland, to help raptor monitoring be as effective as possible in all parts of the UK.

A new approach: patch-based monitoring

BTO and the SRMS started considering ‘Raptor Patches’ – local patches distributed across a wide geographic area that can be monitored through an accessible volunteer survey - a few years ago. Our aim was to gather important data on four widespread species: Buzzard, Kestrel, Sparrowhawk and Raven. These birds were, and still are, under-monitored by existing work, which often focuses on rarer species.

Since then, we have trialled providing free information, support and guidance to help people develop their skills, to recruit and train new raptor survey volunteers. These new volunteers have the potential to transform raptor monitoring, by allowing us to cover more ground and provide better information on many more species. We want and need to extend this network of volunteers across the UK, and make raptor monitoring inclusive to all.

It is vital to have trends for all raptors, across all parts of the UK, to ensure their populations are healthy and provide the knowledge to support their conservation. A patch-based approach is ideal for this, because it offers a bespoke survey design and approach which fits the unique ecology of the raptors they are designed to monitor.

Help us monitor Welsh raptors – take part in Cudyll Cymru

Cudyll Cymru is a new BTO project in Wales, launched as part of our plans to expand dedicated raptor monitoring through our patch-based initiative. The project is open to all levels of experience, including complete beginners, with support and training available for all volunteers.

Benefits of a patch-based approach

There are four main benefits of a patch-based approach: it will help us maintain long-term studies, monitor more species, increase volunteer numbers and create new opportunities for birds and for people.

Maintain long-term studies

There are many highly skilled and dedicated people around the UK who have been monitoring raptors in their area for many years. We need more people trained and mentored to carry on these highly important long-term studies.

Monitor more species

Members of the existing Raptor Study Groups have tended to focus on the rarer raptor species, such as those that require special licences to visit nests. This has left the commoner and more widespread species much less well-monitored around the UK. This is a key gap to fill.

Increase volunteer numbers

Patch-based approaches are also designed with volunteers in mind, helping us to attract and train new raptor monitors and support them in developing field skills, commitment and ownership. In this way, they will help to create greater awareness of raptor monitoring and conservation, and inspire people from all walks of life to enjoy and value raptors.

New opportunities

Raptor monitoring can seem a specialist activity, daunting and difficult. We want to engage with groups who haven’t previously had experience monitoring raptors, including people who live in urban settings. Also, young people love raptors – there’s so much potential for future generations to get involved.

Together, we hope to see a brighter future for raptors in the UK and beyond.

A future for our birds of prey

The work that BTO and our partners are planning is so important in countering threats and ensuring a more secure future for these magnificent birds. It will allow us to understand and mitigate the effects of poisoning and persecution, assess the impacts of land-use change, habitat loss and diseases, and clarify the impacts of onshore renewables development. We will also be able to evaluate the effectiveness of measures taken to support biodiversity, such as protected areas, afforestation and rewilding, for our struggling raptor species.

We want to see decision-makers and conservationists in each country having reliable information at their fingertips, so they can make good decisions to benefit raptors. We want to make sure that the SRMS will play a key part in monitoring the outcomes of grouse moor licencing measures under the Wildlife Management and Muirburn Act for raptors in Scotland. And we want to make sure that the other parts of the UK can also benefit from accessible and rigorous monitoring information.

If you’d like to help us gather crucial data on raptor populations and support conservation that will really make a difference, you can donate to our Raptors Appeal today >

A brighter future for birds of prey

Help us gather crucial data on raptor populations and support conservation that will really make a difference.

Donate now

Share this page