Nightjar

Caprimulgus europaeus (Linnaeus, 1758)

NJ

NIJAR

NIJAR  7780

7780

Family: Caprimulgiformes > Caprimulgidae

This summer visitor, highly cryptically coloured, is more likely to be heard than seen by visitors to its breeding sites, mostly scattered across the southern half of Britain.

Nightjars were once much more widely distributed across Britain than is the case now, occupying lowland heathland and other sites that have been lost to agriculture and afforestation. The very recent increases in numbers and range have been facilitated in places by the availability of recently-felled plantation woodland and climatic changes.

Tracking studies have confirmed that the main wintering area is located in the scrub dominated grasslands, primarily within the Democratic Republic of Congo, that sit to the south of the equatorial rainforest.

Exploring the trends for Nightjar

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Nightjar population is changing.

trends explorerIdentification

Nightjar identification is usually straightforward.

SONGS AND CALLS

Listen to example recordings of the main vocalisations of Nightjar, provided by xeno-canto contributors.

Flight call

Alarm call

Call

Song

Develop your bird ID skills with our training courses

Our interactive online courses are a great way to develop your bird identification skills, whether you're new to the hobby or a competent birder looking to hone your abilities.

Browse training coursesStatus and Trends

Population size and trends and patterns of distribution based on BTO surveys and atlases with data collected by BTO volunteers.

CONSERVATION STATUS

This species can be found on the following statutory and conservation listings and schedules.

POPULATION CHANGE

Following a catastrophic decline in range of more than 50% of 10-km squares between the 1968-72 and 1988-91 breeding atlases, the 1992 national survey revealed a welcome increase of 50% in population size since an earlier survey in 1981 (Morris et al. 1994). A national Nightjar Survey in 2004 revealed that a further 36% increase had taken place in the UK population in 12 years, with a 2.6% increase in the number of 10-km squares occupied (Conway et al. 2007). There was evidence of population declines and range contractions since 1992, however, in North Wales, northwest England, and Scotland. Atlas data from 2008-11 show an 18% range increase in Britain since 1988-91 but some parts of the 1968-72 range remain unoccupied (Balmer et al. 2013). Through its partial recovery of UK range, the species moved from red to being amber listed in the latest review (Eaton et al. 2015).

Although annual nest record samples are very small, nest failure rates have increased and clutch size has decreased slightly. A steep decrease was evident until the early 2000s in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt; a slight improvement in the last ten years has not yet reversed the earlier decrease.

Exploring the trends for Nightjar

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Nightjar population is changing.

trends explorerDISTRIBUTION

Across much of its range, the Nightjar's the breeding distribution is closely associated with lowland heathland and felled or recently planted conifer plantations, though coastal moorland, Sweet Chestnut coppice and sand dunes may also be occupied. In Ireland they mainly occupy clear-felled conifer plantations.

More from the Atlas Mapstore.

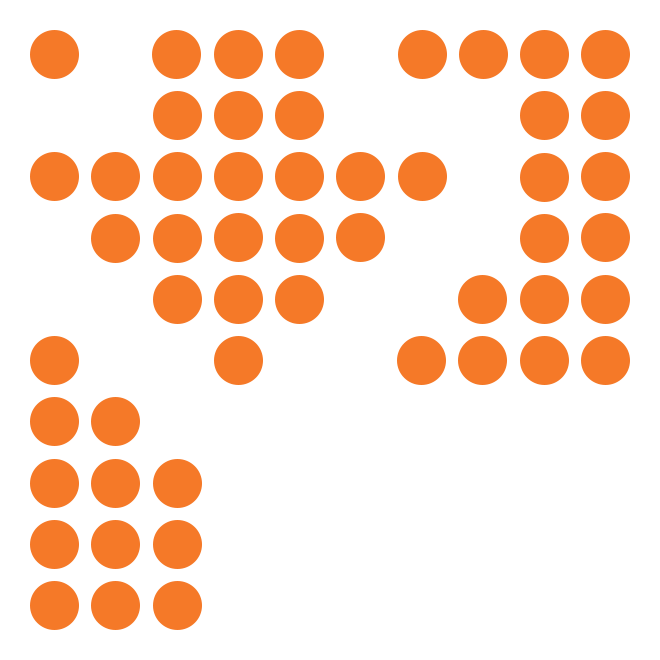

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

| No. occupied in breeding season | 323 |

| % occupied in breeding season | 11 |

European Distribution Map

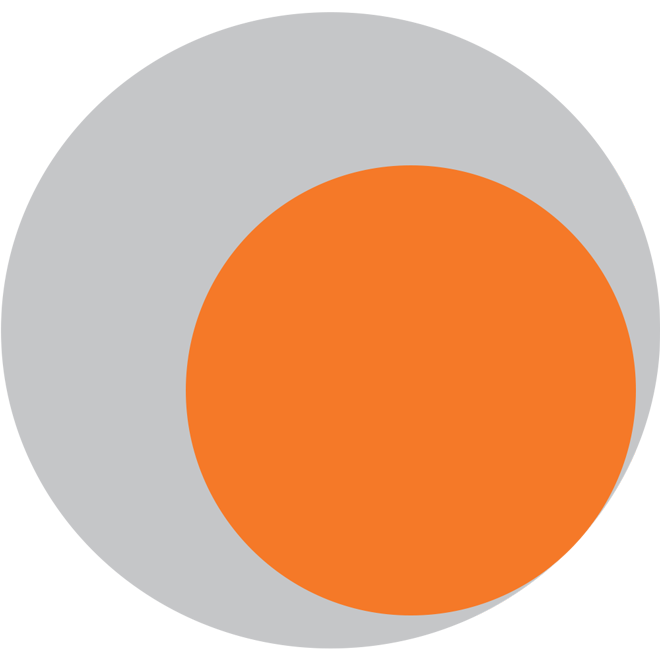

DISTRIBUTION CHANGE

Historically, Nightjars were widely distributed throughout Britain & Ireland but between the 1968–72 Breeding Atlas and the 1988–91 Breeding Atlas the range contracted by 51% in Britain and by 88% in Ireland. More recently, an 18% range expansion in Britain from 1988–91 to 2008–11 sees gains beyond the previous distribution and includes a novel broadening of habitat use whereby moorland conifer plantations are now being occupied; this may assist future range expansion.

| % change in range in breeding season (1968–72 to 2008–11) | -45.5% |

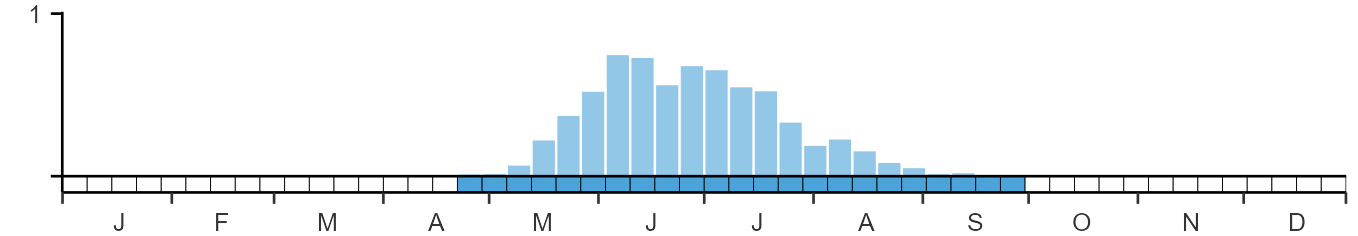

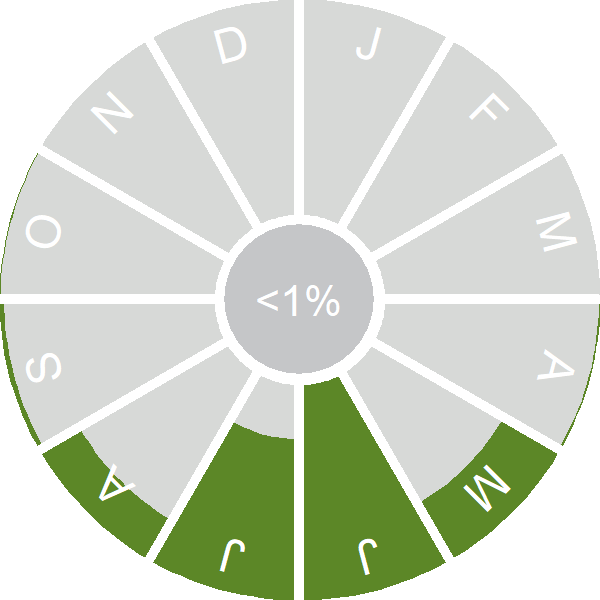

SEASONALITY

Nightjars are summer visitors, present from May to mid August.

Movement

Information about movement and migration based on online bird portals (e.g. BirdTrack), Ringing schemes and tracking studies.

An overview of year-round movements for the whole of Europe can be seen on the EuroBirdPortal viewer.

RINGING RECOVERIES

View a summary of recoveries in the Online Ringing Report.

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Biology

Lifecycle and body size information about Nightjar, including statistics on nesting, eggs and lifespan based on BTO ringing and nest recording data.

PRODUCTIVITY & NESTING

Exploring the trends for Nightjar

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Nightjar population is changing.

trends explorerSURVIVAL & LONGEVITY

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report

Maximum Age from Ringing

|

12 years 1 months 13 days (set in 2012)

|

Typical Lifespan

|

4 years with breeding typically at 1 year |

Adult Survival

|

0.7±0.05

|

Exploring the trends for Nightjar

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Nightjar population is changing.

trends explorerBIOMETRICS

Wing Length

|

Adults | 196.1±5.3 | Range 187–204mm, N=426 |

| Juveniles | 188.9±8.6 | Range 173-200mm, N=81 | |

| Males | 196.1±5.1 | Range 188–204mm, N=323 | |

| Females | 196.3±6 | Range 185–205.5mm, N=100 |

Body Weight

|

Adults | 73.3±7.4 | Range 63.0–88.0g, N=363 |

| Juveniles | 70.8±8.4 | Range 60.0–83.0g, N=81 | |

| Males | 71.9±7 | Range 62.0–86.0g, N=278 | |

| Females | 77.7±7.3 | Range 66.0–90.0g, N=82 |

Feather measurements and photos on featherbase

CODES & CLASSIFICATION

Ring size

|

C |

Field Codes

|

2-letter: NJ | 5-letter code: NIJAR | Euring: 7780 |

For information in another language (where available) click on a linked name

Research

Interpretation and scientific publications about Nightjar from BTO scientists.

CAUSES AND SOLUTIONS

Causes of change

The recovery of this species coincided with the availability of suitable open ground habitat resulting from the felling of forests planted in the late 1920s and 1930s, the clearance and restocking of areas damaged by storms in the late 1980s and, importantly, the restoration of heathland habitats. Management, protection, restoration and re-creation of key habitats remains critical for maintaining Nightjar numbers.

Further information on causes of change

The historical population decline and contraction of range have been attributed to large-scale losses of heathland to agriculture, construction and afforestation (Conway et al. 2007, Langston et al. 2007b). Recovery has coincided with more suitable open ground becoming available through the felling of forests planted in the late 1920s and 1930s, the clearance and restocking of areas damaged by storms in 1987 and 1990 and the restoration of heathland (Scott et al. 1998, Ravenscroft 1989, Morris et al. 1994, Conway et al. 2007, Langston et al. 2007b). While most recent increase has been consolidation within the existing range, there has been colonisation of conifer plantations at higher altitude in southwest England and on the North York Moors: this might be a density-dependent effect as new habitat becomes available or could be evidence of positive effects of climate change (G.J. Conway pers comm).

Prospects for further recovery may be limited, however, due to a reduction of suitable habitat as newly restocked forests grow and to the effects of human disturbance: studies have found that concentrated human disturbance can affect territory densities (Liley & Clarke 2003; Pouwels et al. 2020) and that nest failure is most likely in areas heavily frequented by walkers and dogs (Langston et al. 2007a). However another study, in Thetford Forest, concluded that recreational disturbance was not a factor in nest failure (Dolman 2010), and a study in Nottinghamshire found that, although territory selection was influenced by disturbance, there appeared to be no concurrent impact on breeding success (Lowe et al. 2014). The Thetford study also observed that all nest predators were mammalian (foxes and badgers), but their impact was unlikely to affect Nightjar population size (Dolman 2010). In Switzerland, a study concluded that denser vegetation regrowth and lower prey abundance hindered reuse of previously occupied sites (Winiger et al. 2018); however this was directly contradicted by a subsequent study in the same area which concluded instead that prey abundance had not changed and that recolonization of apparently suitable sites was prevented by light pollution (Sierro & Erhardt 2019).

Burgess et al. (1990) reported that, at Minsmere, creating more edge habitat and providing abundant nest sites resulted in an increase in the Nightjar population (see also Conservation Actions section, below).

New tracking studies suggest that Nightjars consistently forage in non-forest habitats, such as grasslands and semi-natural habitats, sometimes on farmlands, and that the availability and management of the adjacent landscape could affect Nightjar populations (Evens et al. 2017, 2018, Henderson/Conway, in prep.). A small-scale test study in Thetford Forest found that non-forest habitats have higher moth biomass, which Nightjars exploit, although further structured surveys are needed (Henderson et al. 2017). Tracking also suggests that some individual Nightjars may specialise by foraging within one particular habitat type whilst others follow a more generalist approach, and that habitat heterogeneity may help increase local populations by benefiting both specialists and generalists (Mitchell et al. 2020).

Information about conservation actions

Management, protection, restoration and creation (or re-creation) of key forest and heathland breeding habitats remain critical for the long-term conservation of Nightjar (Ravenscroft 1989; Morris et al. 1994; Scott et al. 1998; Conway et al. 2007). Open spaces including clear-felled areas and young stands within larger forests are important, and wide forest tracks can create additional habitat for Nightjars (Verstraeten et al. 2011). Forest management should include rotational cutting to ensure a mosaic of different aged stands are available, as well as actions such as creating glades in woodland and sculpting woodland margins to increase the area of edge habitat, leaving woodland shelter belts standing and providing abundant potential nesting sites, mainly by clearing small patches of heather from the base of small birch trees, (Burgess et al. 1990). In Thetford Forest, Dolman & Morrison (2012) found that density of Nightjars was highest in areas of restock at pre-thicket stages (6-10 years) and that management of conifer plantations plays an important role in determining the population of Nightjars. Radio-tracking there indicated that a variety of growth stages is important for this species and that grazing of open habitats within and adjacent to the forest will also be of benefit (Sharps, K. et al. 2015). Areas of heath and bare sand should also be created or maintained within the open patches (Verstraeten et al. 2011).

As discussed in the Causes of Change sections, both disturbance and light pollution may possibly affect Nightjar density and therefore actions to reduce them may benefit the species, although further research is needed to confirm that these factors do impact on the population. Distance to car park, distance to road and openness all influence visitor density, and therefore changing the location of car parks can be an effective tool to manage visitor numbers (Pouwels et al. 2020)

Recent tracking studies suggest that Nightjars also forage outside forests in grassland and other semi-natural habitats including farmland (Evens et al. 2017; 2018; Henderson/Conway in prep), so the habitat requirements are not necessarily limited to the woodland area in which the birds are nesting, and a wider landscape scale approach may be needed in addition to local site management.

PUBLICATIONS (3)

Flight Lines: Tracking the wonders of bird migration

By pairing artists, storytellers and photojournalists with the researchers and volunteers studying our summer migrants, we are able to tell the stories of our migrant birds, and the work being done

Migratory pathways, stopover zones and wintering destinations of Western European Nightjars Caprimulgus europaeus

Unravelling the mysteries of Nightjar migration

New research involving the BTO has revealed important information about the migration routes and wintering grounds of the Nightjar for the first time. Their main wintering area is now known to be located in the Savannah and scrub forests, to the south of the central African tropical Rainforests, mainly in the southern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo, while key differences were also found between birds' spring and autumn migration routes.

Wind‐associated detours promote seasonal migratory connectivity in a flapping flying long‐distance avian migrant

Links to more studies from ConservationEvidence.com

Would you like to search for another species?

Share this page