How the BTO Acoustic Pipeline is helping to identify some of Europe’s most poorly-known bat species

Be the first to commentStuart Newson is a Senior Research Ecologist in the Data Science and Bioacoustics team, where he is mainly involved in survey design and analyses of data from large national citizen science surveys.

Relates to projects

A trip to a former Benedictine monastery on Lokrum, a Croatian island near Dubrovnik, provided our bat acoustics specialist Stuart Newson with a unique opportunity: to gather recordings of two cryptic bat species, and develop the capacity of the BTO Acoustic Pipeline to identify them.

From the Nunnery to a Benedictine monastery

At the BTO Headquarters in Thetford, we are fortunate to have a roost of Brown Long-eared Bats in the Nunnery buildings where we work. Whilst a lot of research has been carried out on this species, particularly in western Europe, very little is known about the closely related Mediterranean Long-eared Bat.

It is often possible to identify bats by analysing recordings of their ultrasonic vocalisations. Although these sounds are at too high a frequency for most human ears to hear, specialist recording equipment is able to capture the calls for analysis. However, when it comes to the sound identification of the Mediterranean Long-eared Bat, the general thinking is that it cannot be distinguished from the Brown Long-eared Bat – and indeed, other closely related species – because their calls are too alike.

In June, I was given a unique opportunity: to spend a week working on Lokrum, a Croatian island near Dubrovnik, to collect sound recordings for the Mediterranean Long-eared Bat, and a similarly tricky species, David’s Myotis.

The BTO Acoustic Pipeline: our pioneering acoustic monitoring tool

The goal of the trip was broader than this, though. Funded by the Endangered Landscapes Programme (ELP), I was aiming to improve the capacity of BTO’s acoustic monitoring tool, the BTO Acoustic Pipeline.

The BTO Acoustic Pipeline is a powerful species identification tool, which analyses sound recordings and detects the wildlife found in them. It is the result of a decade of work by BTO, building machine-learning algorithms to automatically identify species from sound recordings – from birds and bats to small mammals and bush-crickets.

The focus on species identification means that the Pipeline is a valuable tool to support the ELP, which funds a suite of projects across Europe aiming to restore ecosystems and make them more resilient to environmental change. Being able to monitor how species respond to this environmental restoration work is key to evaluating how effective it is. However, species respond to change over large geographic areas and timescales, making this monitoring challenging.

Acoustic recording and analysis can be an excellent means of collecting and processing data at such large scales. Compared to traditional surveys, acoustic monitoring allows for continuous surveying over long periods with a much lower manual effort, coupled with a higher chance of detecting rarer, less vocal or less detectable species.

By improving the classifiers in the Pipeline – the algorithms which identify species from recordings – BTO can better support ELP’s ecosystem restoration projects in southern and eastern Europe where these two bat species, the Mediterranean Long-eared Bat and David’s Myotis, are found.

By improving the classifiers in the Pipeline – the algorithms which identify species from recordings – BTO can better support ELP’s ecosystem restoration projects in southern and eastern Europe.

To do this, we need good-quality recordings for each of the target species, to train the machine-learning algorithms of the Pipeline to identify and distinguish them from recordings of other species.

Ensuring recordings are actually of the target species, and not of other similar species, is crucial for accurate algorithms. However, there are very few places in Europe where the Mediterranean Long-eared Bat or David’s Myotis can be recorded without also capturing calls of confusion species. The Mediterranean Long-eared Bat and David’s Myotis are not similar to each other, but rather, both have very similar relatives – the Grey Long-eared Bat and the Whiskered Bat respectively.

When I discovered that both these species had a roost in the monastery on Lokrum, I was very excited. These roosts were being studied as part of a project led by Henry Schofield, recent Head of Conservation at the Vincent Wildlife Trust (VWT). Visiting them gave me the rare opportunity to collect sound recordings for the Mediterranean Long-eared Bat and David’s Myotis in the absence of their confusion species.

What do bat sounds look like?

A major purpose of bat vocalisations is echolocation: the sound waves produced by the bat bounce off nearby objects in an echo which gives the bat information about its environment. For most bat species in Europe, the calls made by an individual bat change depending on the environment the bat is flying in, allowing the bat to collect the most relevant information about its surroundings.

In closed environments, like dense woodland or a confined roof space, bats produce very short calls which cover a broad band of frequencies (known informally as pitch). This type of echolocation call provides the bat with very detailed information about its close surroundings.

When the same bat flies into a more open environment, the band of frequencies covered by the calls is reduced, whilst calls become longer in duration. The echolocation now provides the bat with less detailed information, but that information covers a greater area.

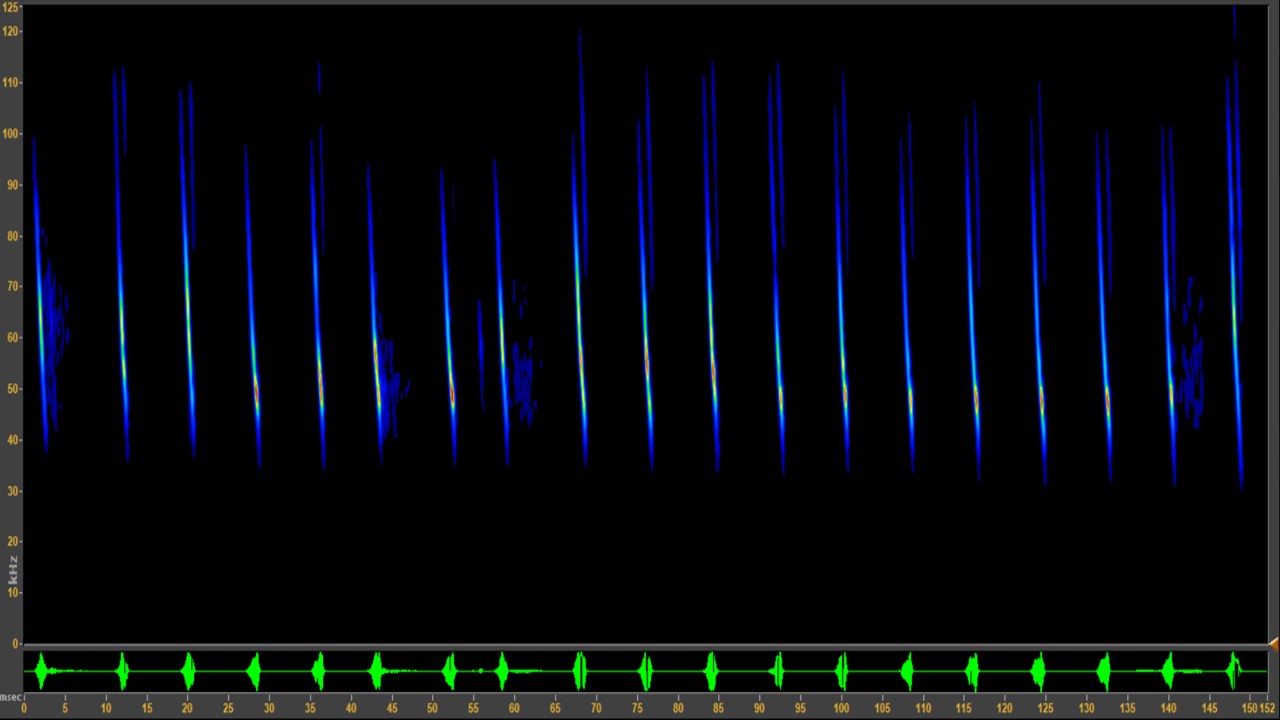

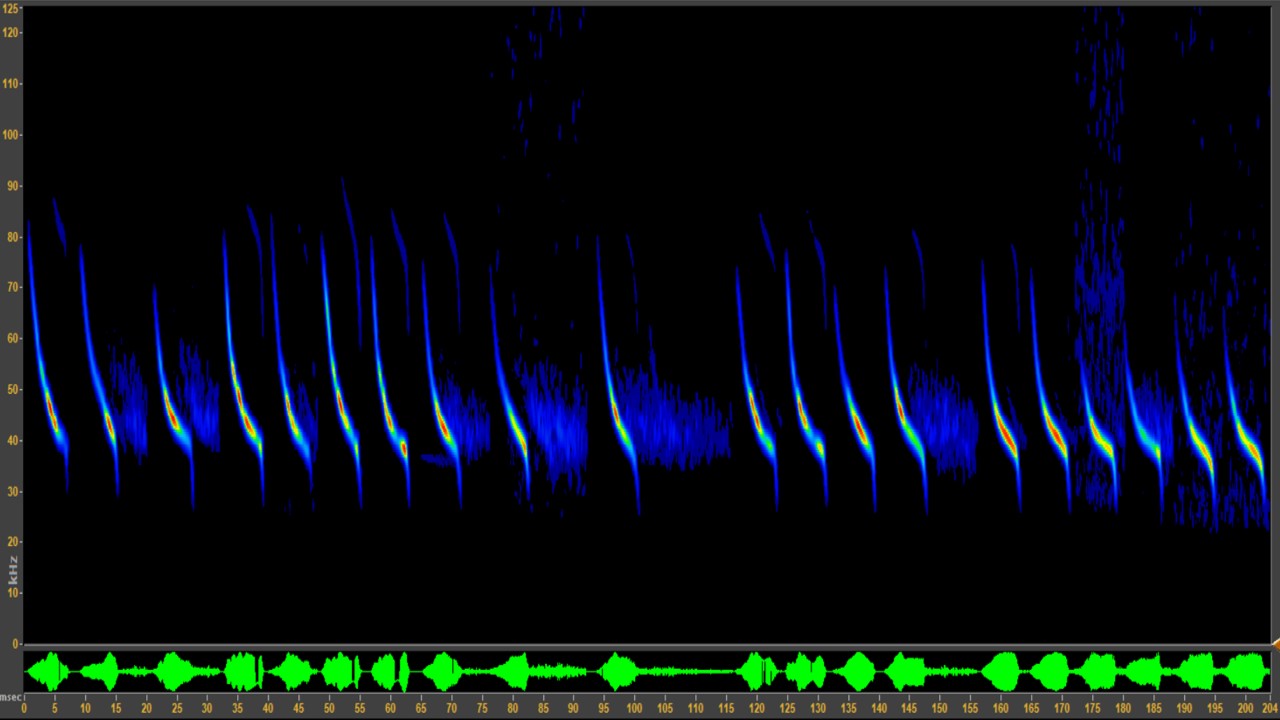

Bat calls can be viewed on a type of chart called a spectrogram: a visual representation of a bioacoustic signal.

The different calls can be viewed on a type of chart called a spectrogram. This is a visual representation of a bioacoustic signal: a sound’s frequency on the vertical axis, amplitude (or volume) depicted as the intensity of colour, and how these change over time, along the horizontal axis.

The spectrograms here depict short- and long-duration calls of David’s Myotis. When comparing the two spectrograms, the greater range in frequency in short-duration calls is visible in the taller ‘lines’ of sound, and the length of long-duration calls is reflected in the greater width each sound occupies.

Collecting recordings from the monastery

When I am recording bats around their roost sites, I need to apply this knowledge of different call types to make sure I capture, as far as possible, the complete range of calls that the bat species can produce. Normally, I would spend a couple of nights with a thermal camera, watching the bats leave and return to the roost to map their flight routes through different environments and identify areas where the bats produce the different types of vocalisations.

However, with the VWT’s knowledge of the roosts, there was already a lot of detailed information for me to start with. Working alongside VWT, I positioned our bat detectors carefully, choosing locations where we thought the bats would produce their full range of calls, from short- to long-duration echolocation calls as well as social calls.

I also had to be mindful of the immediate area around the recorders. Ideally, bat detectors or microphones should be at least 1.5 m up from the ground and away from any flat surfaces, including tree trunks and vegetation. Poorly placed recorders give us heavily distorted sounds, due to soundwaves refracting off these surfaces – these are difficult to identify or use for training algorithms. Fortunately, knowing how to avoid these problems, my recording efforts were successful!

Working together for bats

Thanks to the funding from the ELP, we were able to collect some high-quality recordings for both the Mediterranean Long-eared Bat and David’s Myotis. We’re now working with these recordings to update the BTO Acoustic Pipeline algorithms used for all European countries and regions where these species occur.

With the improved algorithms, and our new understanding of the sound identification of these species, we have a much better chance of identifying these species from acoustic recordings. In turn, this will make it possible for future ELP projects to monitor how their restoration activities might be helping these species recover in degraded habitats.

The ELP funding has enabled us to collect or collate recordings for six of the most cryptic bat species in Europe since our previous blog in October 2022, and dedicated recording collection work is only required for two more (excluding five island endemics). But these species, the Alpine Long-eared Bat and Anatolian Serotine Bat, remain two of the most challenging.

The work described in this blog was undertaken by Stuart Newson (BTO) in collaboration with a team from the Vincent Wildlife Trust, led by Henry Schofield. In addition to the help that VWT has provided, Stuart would also like to give particular thanks to Henry and to Chris Damant from Bernwood Ecology for the use of their photos here. The spectrograms shown here were produced in SonoBat.

This project was supported by the Endangered Landscapes Programme, managed by the Cambridge Conservation Initiative in partnership with Arcadia, a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin.

BTO Acoustic Pipeline

From backyard sound projects to commercial bat surveys, the BTO Acoustic Pipeline provides tools for the detection and identification of birds, bats and other wildlife in both audible and ultrasonic sound recordings.

- Accurate species identification and data management for acoustic monitoring, in conservation, management and site assessment.

- For individual, commercial and large-scale use, with free and paid plans.

Share this page