BirdTrack migration blog (mid July–mid August)

Over the summer months, migration is almost at a standstill – at this time of year, breeding is the main focus with parent birds busily raising their offspring.

Cuckoos

Cuckoos are an exception to this, leaving their young to be raised in the nests of other birds. Arriving in Britain and Ireland to breed from the end of April, the bulk of the population has reached our shores by mid May. By the end of June, sometimes only six or so weeks after arrival, many of these birds will have started their return journey to central Africa. Satellite tracking data, collected as part of our Cuckoo Tracking Project, have shown that there is some variation in the timing of individual birds’ departure, with some leaving 2–3 weeks before others.

The data also show that birds take one of two main routes when migrating back to the Congo Basin. One course takes Cuckoos south-east of Britain and down through Italy before crossing the Mediterranean Sea; another takes a more westerly line through Spain and then across to north-west Africa. At the time of writing, at least two of this year’s tagged Cuckoos appear to be heading for the westerly route, which is associated with higher rates of mortality.

Follow the birds in real-time as they head towards their perilous Sahara crossing on the Cuckoo Tracking Project map.

Waders

The past couple of weeks have also seen waders begin to head south. Green Sandpiper and Spotted Redshank are typically the first species to start their migration after breeding in waterlogged wooded areas in northern Europe and across the arctic tundra respectively. Spotted Redshanks arriving in Britain and Ireland at this time of year are typically female birds; chick-rearing is left solely to the males, which remain behind to raise their offspring and so depart from the breeding grounds later.

Passage waders seen at this time of year are likely to be failed breeders, or immature birds which did not complete their migration to their breeding grounds.

Reports of both Green Sandpiper and Spotted Redshank have increased recently, and we can expect them to continue to do so until late August and into September as adult birds are followed by this year’s young.

The number of reports of other waders has also increased as Ruff, Curlew, and Dunlin start to pass through. These birds will mostly be failed breeders, or immature birds that never completed the full migration to their breeding grounds.

Seabirds

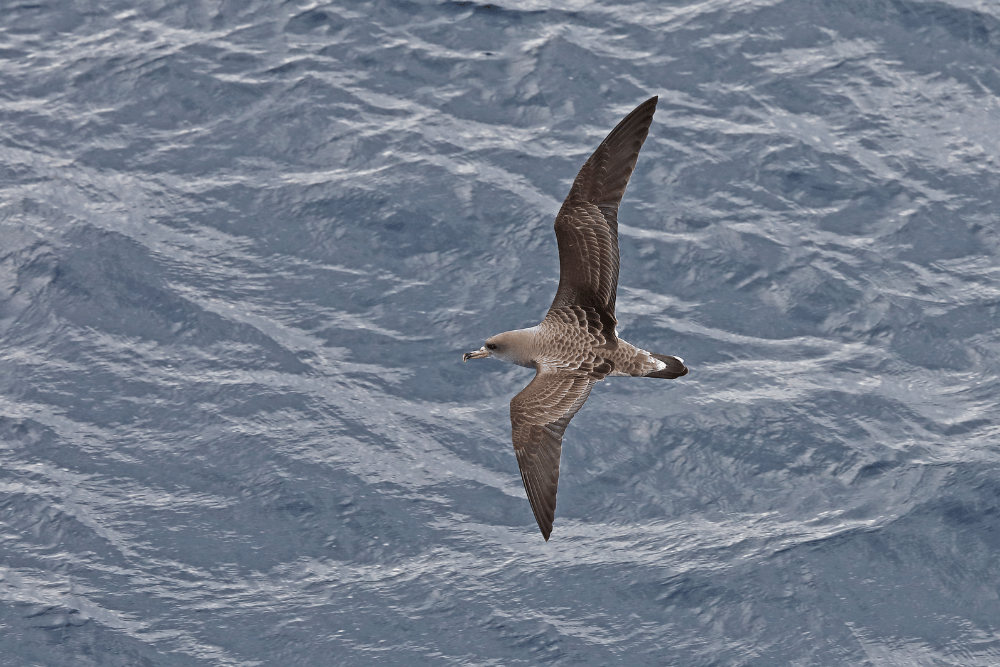

The start of July saw the first hints of seabird passage, with a scattering of reports of both the larger shearwaters, Cory’s and Great Shearwater. Neither of these species breeds in Britain and Ireland, but they do visit our waters as part of their migration.

Cory’s Shearwater breeds on many of the Atlantic islands, including the Azores and the Canaries. Between June and October, large gatherings of these shearwaters can build off south-western Britain. The exact origins of these birds are still unknown, but the large flocks can result in a large number of records from coastal locations in that area. So far this year the number of Cory’s Shearwaters reported has been low, but it is still a little early in the season.

In contrast, Great Shearwaters breed on islands in the southern hemisphere. At this time of year, these birds undertake a huge migration up the west coast of Africa and across to the eastern seaboard of the USA, then east to the waters of western and south-western Britain and Ireland. As for Cory’s Shearwater, reports of Great Shearwater have been low but are likely to increase in the next month.

One species that was fairly well reported from typical seawatching hotspots such as Pendeen and Porthgwarra (Cornwall) and Galley Head (County Cork) was Wilson’s Petrel.

Like Great Shearwater, Wilson’s Petrel breeds in the southern hemisphere and migrates across the Equator to spend several months in the waters of the North Atlantic. Sightings of this seabird are much-prized by birdwatchers in Britain, and the species has an almost mythical status for many.

Once, it was only possible to see this species from special boat trips from the Isles of Scilly, but in the past few years the number of annual records has increased and birds are even seen regularly from land. This year is no exception, with over 30 birds seen from watchpoints in south-western Britain and Ireland so far.

Swifts

You didn’t need to head to Cornwall or southern Ireland to witness migration, though.

Screaming flocks of Swifts are a wonderful feature of birding at this time of year.

Late June and early July saw a steady increase in reports of Swifts. Screaming flocks of Swifts are a wonderful feature of birding at this time of year, as adults are joined by their young and groups merge and roam together before starting their southward migration.

By the end of July, almost all of our breeding Swifts will have departed, and it will mostly be later breeding birds migrating through Britain and Ireland from more northerly populations that are seen in our skies.

Passerines

Many of our summer migrants will have fledged their first broods and will be in the throes of nesting again. Some species may even raise three broods of young, as in the case of House Martin.

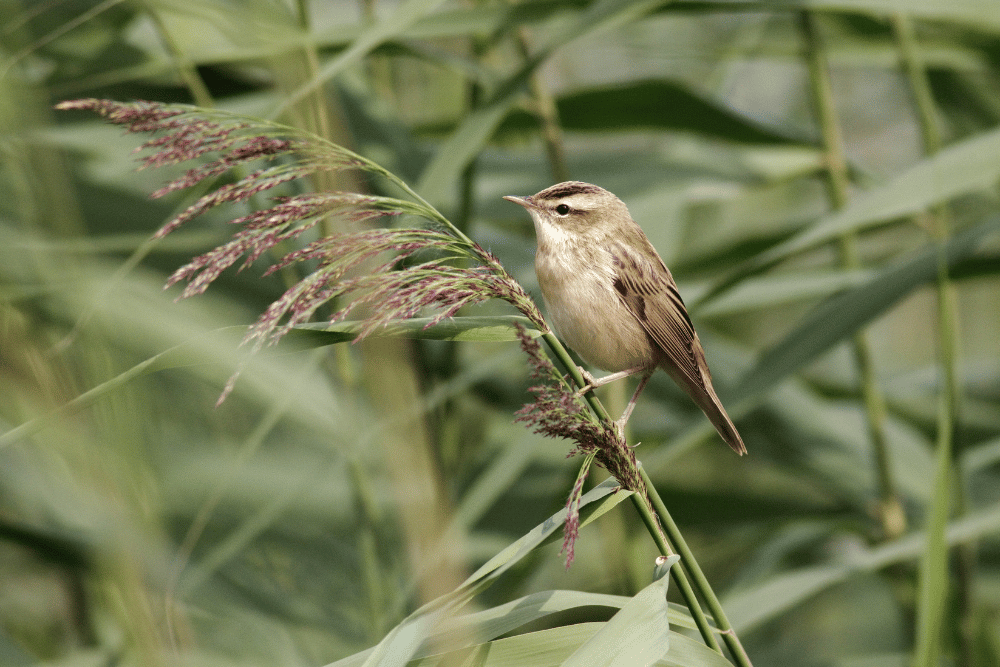

Those young that have already fledged will begin to disperse away from the areas where they hatched and sometimes turn up far from their typical habitats. Species to look out for include Sedge and Reed Warbler, Blackcap (with the young having the same rusty cap as adult females), Chiffchaff, Willow Warbler, and Whitethroat.

A few rarities were seen during the last month with the 13th Pacific Swift for Britain being found in Shetland. An adult Roller on the Isle of Wight would have proved a bigger hit with twitchers had it been found on the other side of the Solent.

A brief Marsh Sandpiper in Kent was most welcome, as were a scattering of Caspian Terns including two groups of two in Norfolk and Northumberland.

Looking ahead

Late summer can be likened to late winter, in that the promise of migrant birds is just around the corner – but just as we see with spring migration in early March, in late July autumn migration can take a little while to get going. The next 3–4 weeks will follow a similar pattern to those just passed, with the main species migrating being waders and seabirds. However, it is also a good time of year to look out for gulls.

Yellow-legged and Caspian Gulls are close relatives of the Herring Gull. Towards the end of summer, numbers of both these species start to build, mainly in the south-east of Britain, as juvenile birds disperse from their hatching grounds. Although they can be tricky to tell apart from other large gulls, with a bit of practice it is possible to pick both species out from their commoner cousins.

At the other end of the size scale, Little Gull is a regular passage migrant, and from late July flocks of these dainty birds can be found at both coastal and inland locations where they will hawk for insects over water. Flocks of gulls will often feast on swarms of emerging flying ants, and it is always worth checking these groups for Little Gulls. The adults’ pure white wing tips look almost translucent when seen from below and are a good distinguishing feature, together with the species’ smaller size.

The number and range of wader species on the move will continue to build through July and into August, with Common Sandpiper, Whimbrel, Greenshank, and Ruff all beginning migration. Juvenile birds will pass through a little later than adults, their fresh plumage distinguishing them from adult birds in worn-out breeding plumage or even moulting into their winter dress. Scarcer species to look out for include Red-necked Phalarope, Pectoral Sandpiper, and White-rumped Sandpiper.

If seabirds are your thing, then heading to the coast at this time of year can be rewarding with a range of species starting to turn up. Balearic Shearwater is a close relative of the more familiar Manx Shearwater, with its critically endangered population numbering a mere 9,000–13,000 mature birds.

Each summer, Balearic Shearwaters undertake a post-breeding migration, leaving the Mediterranean Sea and gathering in the North Atlantic. It is at this time of year that birds start to be recorded off the coast of southern Britain, and sites like Portland (Dorset), Strumble Head (Pembrokeshire), and Selsey Bill (West Sussex) are prime locations to look for them, especially during strong south-westerlies.

Send us your records with BirdTrack

Help us track migration amidst an outbreak of avian influenza.

Submitting your sightings to BirdTrack is quick and easy, and gives us vital information about our breeding and migrating birds.

Find out more

Share this page