Some species that we think of as residents also undertake movements at certain times of year. These are known as seasonal movements.

Winter

In the winter, migrant birds from other populations in Europe boost populations in Britain and Ireland. These movements are often related to severe periods of weather or a shortage of food.

Lapwing

Lapwing is a good example of a species that can be affected by severe cold weather, causing populations on the Continent to evacuate their traditional wintering areas and move westwards to Britain and Ireland in search of milder conditions. They usually return to the Continent when the conditions improve, often before the spring.

Lapwings breeding in Britain and Ireland are partial migrants, with many remaining through the winter close to their breeding grounds whilst others migrate. Information from ringing shows that Lapwings from the north and north-west of Britain move westwards in the autumn, with some going to Ireland and others into France and Iberia. Lapwings from the south-eastern part of Britain move mainly southwards to France and Iberia.

Siskins

Siskins that breed in Britain and Ireland generally winter near to their breeding areas, although some movements are made on a north-south axis, depending on food supplies and weather conditions. A few of our breeding birds go as far as the Low Countries, France and Iberia to winter.

Information from ringing shows that during the winter, large numbers of Siskins from Scandinavia join our population. The pattern of ringing recoveries suggests that some birds from Scandinavia move south to the Low Countries before crossing to England and some will continue towards Iberia and even as far as the Mediterranean and Central Europe.

Starlings

From late summer, migrant Starlings from as far as Scandinavia, the Baltic States, the Low Countries, Germany, Poland and Russia join our residents. By mid winter the population can be huge with up to half a million roosting in some places.

The map shows the movement of Starlings from a broad geographical area into Britain and Ireland.

Birds on passage

Some species pass through Britain and Ireland in the spring and autumn but do not linger here to breed. Classic passage species are Little Gull, Black Tern, Pomarine Skua and Long-tailed Skua. These species breed further east in eastern Europe, Scandinavia and into Russia yet their migration route brings them through Britain and Ireland.

The weather plays an important role too and periods of easterly winds in the spring are more likely to bring Little Gulls and Black Terns to us. Small numbers of Little Gulls also winter off our coastline but it is primarily a passage species.

During the spring and autumn, many waders pass through Britain and Ireland on their way from breeding grounds in the high Arctic to wintering grounds further south. For some wader species like Dunlin, Sanderling, Grey Plover, Turnstone part of their population chose to winter here whilst another part of the population will continue south and winter in Africa.

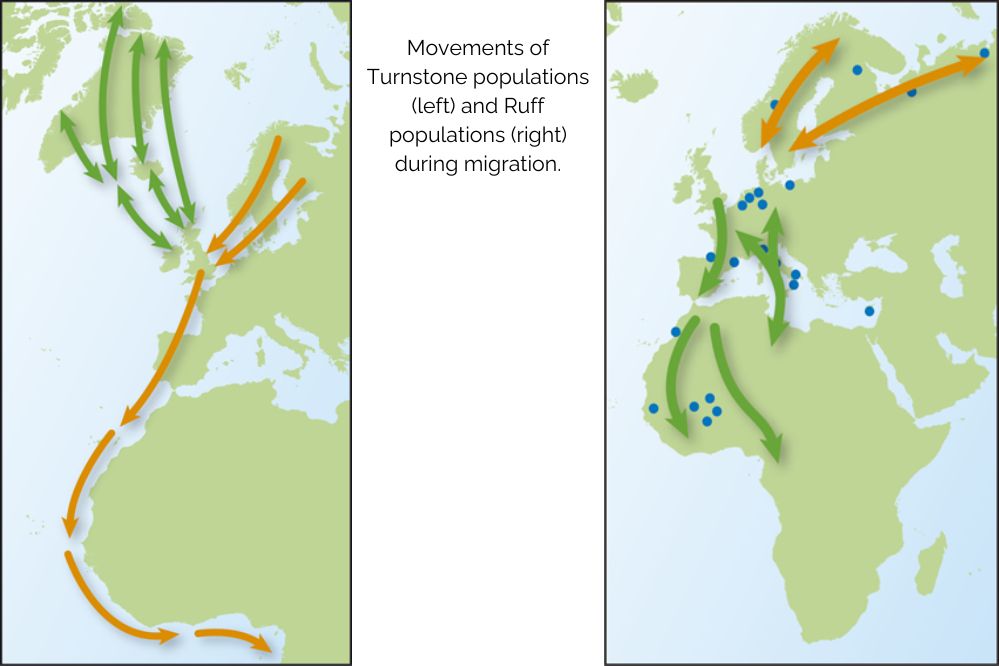

The two maps here show the different strategies taken by two species of wader; Turnstone and Ruff.

The Turnstone map shows two populations; birds breeding in Greenland and arctic Canada, which will winter in Britain and Ireland (green arrows), and birds breeding in Fennoscandia, which will pass through Britain but will continue south to winter along the coast of West Africa.

A very small number of Ruff breed in England so most of the birds we see are passage migrants. Numbers in spring are quite low but the autumn passage is much bigger and a few even stay here all winter. Ruff breeding in Scandinavia and Arctic Russia pass through Britain and the Low Countries on a broad front and winter in Africa from Senegal east to Mali.